My Week at the Muay

Thai Institute

Bernie Gourley

The

Gi Yu Atlanta Dojo

03/18/13

Bas-relief

on the MTI façade

Why I Went

I was in Cambodia and Thailand last

October. During that time, I spent six days training at the Muay Thai Institute

(MTI) in Rangsit, Thailand. Sandhu-sensei asked me to write about my

experience.

Let me begin by discussing why I did

this. I was motivated on several fronts. First, I enjoy learning about almost

everything (e.g. I also attended a one-day Thai cooking class.) Second, I’m writing

a novel that features a Muay Thai (MT) master in a supporting role, and so

there was a research component to the trip. Third, it seemed like a good idea

to learn more about this style, which is widely practiced and much-emulated by

brawlers, given that I study jissen

(real fighting) budō.

However, the dominant reason was

that I believe in regularly stepping outside of my comfort zone. I went in

order to collect an experience that would force me to view myself (and familiar

problems) in a new light. Not long ago I read a biography of Miyamoto Musashi, and

I began to see how what he did and didn’t value in life helped make him the

warrior he was. He could’ve made a buku of koku

(i.e. a big salary) as a retainer, but he opted to walk around the country in

what we would today consider abject poverty in order to challenge himself. Don’t

mistake me, I’m not extolling poverty as a virtue. What I’m saying is that if one

values being comfortable (whatever that may mean, individually) over seeking

challenges, one’s growth will always be limited.

I think the greatest gift I’ve

received from my training is the ability to adopt this life philosophy. I’m a

shy and timid person by nature. However, everything we do in the dōjō trains us to live boldly. I’m not

just talking about actions like stepping out of the way of a bokken as it races towards one’s head.

That’s only the most obvious type of example. Learning to ki-ai with spirit, learning to say “onegaishimasu” loud and clear and like I meant it (rather than

mumbling it in fear that I’d mispronounce it or my tongue would trip over the

words—as has happens to me periodically), these actions, too, have played a

role in making me confident enough to face down my inner demons.

Before I move on, it’s worth

stating a few words about what I was NOT after. First, I wasn’t shopping around

for another martial art to devote myself to. When and if I’m back in Thailand,

I would train at MTI again in a heartbeat, but I have no intention of dividing my

precious and limited resource of training time into yet smaller slices. I knew

going in that MT would not be my ideal martial art for reasons that I’ll discus

later. Second, I didn’t pursue this training because I thought I had some big

gap for which I was hoping to cobble together a fix. If anything, I’ve always

worried about my personal inability to do justice to the huge amount of

material that we already have within the schools we study. While I make sure I

do some sort of training every day, whether I’m in the dōjō or not, I’ve never felt that I had such a command of the

schools we study that it was time to collect yet more techniques. In short, I

don’t want to be the type to collect a dozen different black belts, but have every

movement that comes out of my body be muddled, homogenized, and unpracticed.

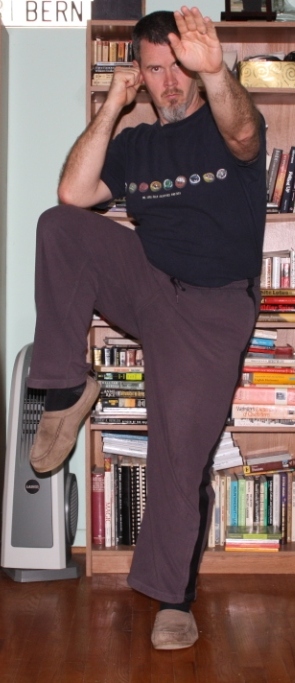

We bounced on those

tires to develop footwork rhythm and to tighten our calves.

The training

I trained 4

hours every day while I was at MTI. This was the typical (and recommended) schedule

for visiting students. The Institute ran four 2-hour sessions per day, and they

were open seven days a week. However, it was recommend that one train only six

days a week, at most, and most people did five or six day training weeks. A few

trained three sessions per day (i.e. 6 hours/day.) The Thai kids generally

trained only one session per day after school. I trained during the 7 to 9am

and 3 to 5pm classes.

The

training always began with a warm-up. The warm-up began with about a fifteen

minute run that was immediately followed by bouncing footwork drills on truck

tires laid flat on the floor. We would then do a stretch designed to loosen the

hip so that it could roll over for the MT style roundhouse kicks. This involved

standing on the floor and putting one foot up on the ring (between 3 and 4 foot

high) with the toes pointed up. One then rolled one’s leg inward so that the

inner edge of one’s foot touched the ring platform. As one did that, one pivoted

on the ball of the support foot as one would when kicking. Simultaneously, one

moved one’s hands into guard positions for this kick (i.e. the [initial] lead

hand comes back to one’s ear as the other hand sweeps down outside one’s

kicking leg.) We did 30 of these stretches per leg. Sometimes we would then

practice alternating knee strikes, bringing one’s knee up to about chest level.

After that, we’d get our first two-minute water break.

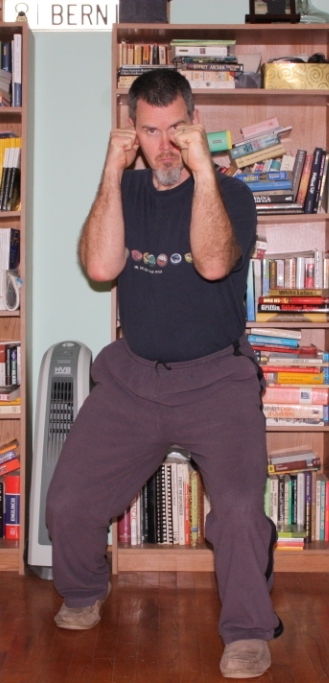

The basic MT guard

posture in forward, right side, and left side views

After warm-ups, the next thing that

level-one and -two students did was footwork drills. For a beginning level-one

student, one started by just holding one’s guard as one practicing stepping and

maintaining the proper interval between feet. We did several basic types of

footwork, forward-back maintaining a lead side, forward-back alternating (i.e.

lunge footwork), side to side, and circling around an opponent. On successive

runs of the drill, one would begin

delivering one strike (or defense) as one stepped, and then

one would build into progressively more complex combinations of strikes. The

weapons were fist, elbow, knee, shin, and foot. There were jabs, crosses,

hooks, uppercuts, roundhouse kicks, lead knee strikes, rear knee strikes, and

push kicks (lead and rear.) One worked through these various permutations using

the three footwork types.

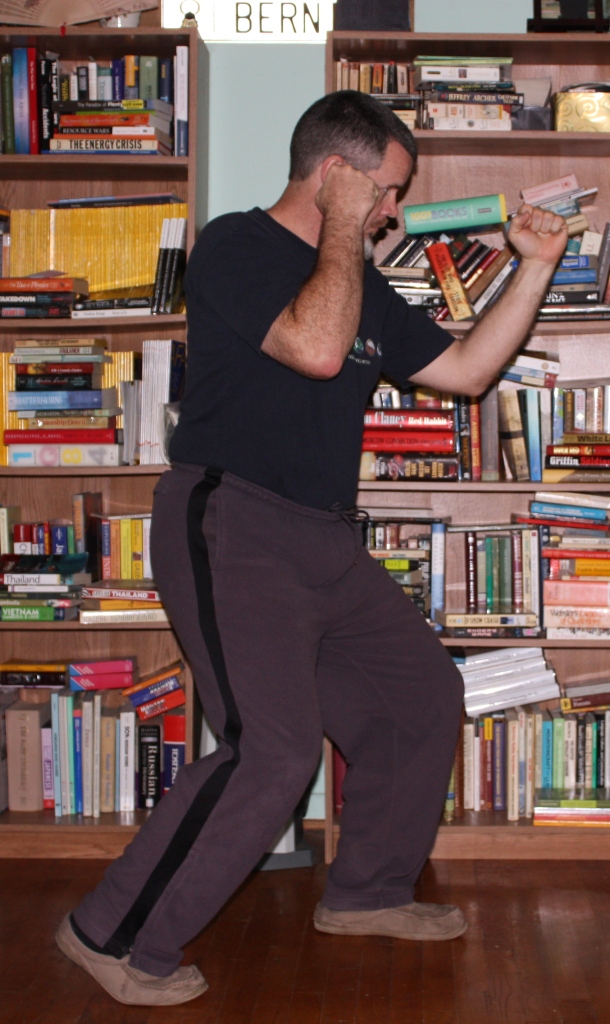

There were also defenses to

practice. These included: lead-hand high-level deflections, lead-hand low-level

deflections, rear-hand high-level defections, rear-hand low-level deflections,

and a guard against roundhouse kicks that involved extending one’s lead hand

like metsubishi while lifting one’s

rear knee to one’s elbow such that the opponent’s kick would land on one’s shin

or forearm and not one’s ribs or neck.

Defending the

roundhouse kick

Sometimes the instructors would put

steel rods that were about hand-width into our hands as we practiced these punching

drills. On occasion a chair or a cone would be used as a range reference and we

would practice circumnavigating that reference point while delivering strikes.

Alternatively, one might practice advancing into range while striking and then

back out while striking.

After

footwork drills, beginning students usually put on hand wraps and gloves and drilled

on the heavy bag. Often this began with two students facing across from each

other to either side of the bag with one student holding the bag; we’d then

alternate kicking the bag with a roundhouse kick on one side. We’d do 50 per

leg, and then rotate until each member of the trio had kicked with each leg.

After that, the drills were a similar series of combinations to those we

practiced in the footwork drills, but done while delivering the strikes to the

bag rather than in air. This allowed one to work on power, but with less

freedom of movement.

Because I

was there only a short time and was not in a certification track, they

reclassified me as a “freestyle” student about half way through the week so

that I would have a broader experience. From that point on, focus-mitt drills

and shadowboxing became a part of the training. Focus-mitt drills involved the

instructor extending out one of the MT pads at some orientation, and one would

deliver the appropriate strike depending upon its position and orientation. I

found this type of drill, which I haven’t done much of, to be extremely

beneficial. One has to recognize a target and act quickly upon it.

I must admit that I never really

understood the value of shadowboxing before my visit to MTI. I thought of it as

a sort of solo training that one does when one doesn’t have a training partner

at the moment—better than nothing, but just a make-do exercise. However, I

learned that there’s a lot of strategy involved in moving around the confines

of a ring, and Thaiboxers use shadowboxing to engrain in themselves good

strategy so that they don’t have to consciously think about it under the

pressure of the fight.

I also did “sparring” on one occasion; though

it wasn’t the free-form sparring that one would think of, but much slower and

geared primarily toward teaching.

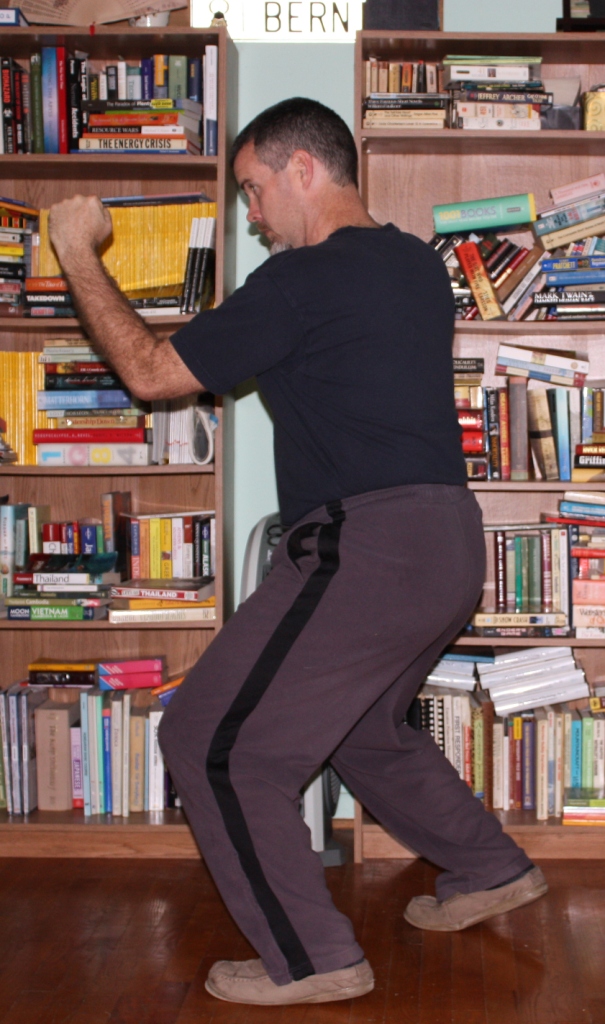

Besides the support

leg heal being up, this may look familiarish.

Myths and

Misperceptions

There’s an old story that has been

told in both the Taoist and Zen Buddhist traditions. I’m sure most of you have

heard it. It’s about a cocky young student who goes to learn from a master, but

the student adopts the attitude that the master “won’t have to teach him much,

because he’s already got a solid foundation.” The master pours some tea for the

student, and soon the tea is overflowing the cup and scalds the student’s lap.

The master tells the young man that he cannot learn unless he first empties his

cup. Cognizant of this, I tried to go in with minimal preconceptions. Still,

one always carries some mental baggage with one, and what’s important is one’s willingness

to jettison preconceptions that prove wrong.

A few of my expectations proved wrong.

First, it seems to be widely

believed that MT practitioners aren’t diligent about mechanics. In other words,

critics say that MT fighters are fundamentally brawlers and don’t trouble

themselves with the minutiae of proper technical detail. MT is widely practiced,

and some of these critics may be speaking from perfectly correct--albeit

anecdotal--experience. My experience was different. The instructors at MTI were

meticulous about the details. If I was in guard and my elbow drifted an inch

from my ribs, I heard about it (i.e. and sometimes felt it.) If my feet were slightly

too wide or too narrow, I heard about it.

At MTI they’re struggling with the

fact that the MT genie is out of the bottle, but they would like to standardize

a curriculum globally so that the art doesn’t degrade into a muddle (part of

this is reflective of a desire to see Muay Thai in the Olympics.) The

instructors can’t really succeed at this point in standardizing a curriculum

that will apply to a MT gym in a strip mall in Chicago or a basement dōjō in Prague, but they do what they

can. And all they can do is to make sure that students running through their school

have a set of basics drilled into them.

Second, I

expected MT fighters to have zero grappling skill. It’s true that Thaiboxers generally

don’t have much grappling game. Practitioners consider MT to be a system of

self-defense and the descendent of a combat art, as well as being a sport.

However, in reality their style is shaped by the rules of their sport more than

by the dictates of real world attackers. The rules of the sport allow and

encourage takedowns, but once a fighter is on the ground the match resets. There’s

one area of grappling in which at least a few Thaiboxers are quite skilled, and

that is doing take-downs using techniques that are similar to our ko uchi gari and ko soto gari. To be honest, in the twenty-some fights that I

watched while I was in Thailand, most fighters seemed to ignore this skill in

favor of exchanging knee strikes when they’d get into a clinch. Maybe they

found it to be a low-success / risky maneuver. However, a few were very

effective with takedowns.

Third, I

expected some of the training might be brutal on the body, and that toughening

weapons might be part of the drill. MT is legendary for steel-shinned fighters.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, YouTube search, “Crazy Man Kicks Down

a Banana Tree.” At MTI, however, there

was as much focus on safety as anywhere I’ve trained. In sparring, shin guards

were often worn, and we didn’t kick anything harder than a heavy-bag with our

bare shins.

Fourth, I

thought there would be no practitioners who were my age. It’s true that there

are few competitive fighters who are even in their 30s, let alone their 40s,

but there are some people who continue to train into their golden years. The

oldest instructor was about 70. As an aside, Master Ravee (the septuagenarian)

was a fascinating man. He had a 220 fight career. He won almost 80% of his

fights and held the Middleweight title for a while. (Note: That might not sound

impressive by today’s standards, but Thaiboxers have been known to do as many

fights in a week as a typical MMA fighter does in a year [e.g. 4].) Master

Ravee was legendary for his use of elbows. I’ve forgotten what his knockout and

TKO rate was, but it was staggering (i.e. something like 2/3 or ¾ of the fights

he won.) I think, but am not absolutely sure, that they fought mostly in rope

hand-wraps back in his day. Such ropes helped keep the little bones in one’s

hand from breaking, but didn’t really improve the civility over bare-knuckle

boxing.

One

preconception that was confirmed was that MT practitioners are, on the whole, extremely

fit. The instructors generally taught all four classes a day. My primary

instructor, Master Dang (a 400 fight career and the same age as me), ran the warm-up

with us each session, and then I’d see him in the evening or morning as he did

his “serious” run. My room overlooked the gym, so I’d occasionally see instructors

or fighters working the bag after hours. In short, they were machines.

My Perceptions of Muay

Thai

Now we get

down to brass tacks. What did I think of MT as a martial art? I think that,

within their domain, Thaiboxers are a force to be reckoned with. Most of them

are highly skilled, strong, and tough as nails. Within their domain, I think

they can hold their own among those of any martial art. Why don’t I take up

Thaiboxing then? Because the domain in which they are extremely skilled is dangerously

small for someone interested in jissen.

Let me explain what I mean by

“domain.” If one could imagine all the possible combative situations one might face

and the varying skills one would need to deal with those situations, there is a

universe of combat skills. Different martial arts take on different sets within

that universe and explicitly practice to survive certain types of combat

encounters. Our art has a huge domain. We have specific techniques for: rear attacks,

multiple attackers, fighting on the ground, fighting standing, and even for fighting

submerged under water. We fight with spears and unarmed against people who have

spears. We use firearms, and practice disarming those who employ firearms against

us. We even have the odd technique for taking out a sentry.

A Thaiboxer’s domain is a single

unarmed attacker who, granted, uses many body parts as weapons. However, their

domain also subtracts out many attacks prohibited by the rules (e.g.

intentionally striking the crotch, intentionally striking the neck, choking the

opponent, etc.) It’s true that there is

carry over from the set of skills one explicitly practices to situations more

broadly. For example, fighting against a dog is not in the domain of skills

that I practice, but I suspect my chances are at least marginally better than

someone who spends their evenings sitting on the couch with a bag of Lays. (However,

not so good as someone who practices those skills specifically.) One does what

one trains, and if one’s domain is very limited one better hope one’s

opposition sticks to conventional attacks.

I will readily admit that there is

a cost to having a vast domain. One has to spread one’s limited time resources

more thinly over a broader base of skills. However, I think if one’s interest

is in jissen, one has to be ready for

quite a range of threats.

Another difference between what

Thaiboxers do and what we do is in the mode of mindset and strategic approach.

I think of this in terms of having a coup

de grace mindset versus having an endurance mindset. Professional bouts

consist of five three-minute rounds. Youths often do three three-minute rounds,

and one sees some variations. As you probably know from randori keiko (free sparring) going that long constantly exchanging

blows with only short breaks is very tiring. Therefore, the MT approach to

movement and striking is as much designed to keep one on one’s feet as to

deliver damage. In jissen, one has to

cultivate the ability to strike powerfully and end fights definitively and

quickly. That doesn’t mean that one always goes this route, but conditions may

require it. The opponent may have backup on their way. In combat with lethal weapons, the more

opportunities the opponent gets, the more likely it is that you end up in a body

bag. So there are a number of reasons that we train to be able to end the fight

decisively, even if that incurs a risk.

What our arts have in

common

Having

discussed some differences between our martial art and MT above, it’s worth noting

some similarities. In terms of mechanics, there are a number of similarities--the

human body is, after all, the human body. Their knee or elbow strikes aren’t

substantially different from the way we do them. However, I’d like to focus on

something other than the physical similarities.

I noticed a confidence and clarity

of action among the instructors and many students that wasn’t different from

any other diligent martial artists.

Wai Khru in progress

While their

rituals may look strange and incomprehensible, I think there’s a lot more

commonality in mental approach than one might expect at first blush. The Wai Khru is a great example of this. If

you’ve seen MT bouts, you’ll recall that at the beginning of each fight they

play a shrill flute and drum music and there’s a ritual that usually includes a

dance that each fighter carries out. If you haven’t seen a MT match (or you’ve

only seen one in the US—I don’t know that they routinely do Wai Khru here), you can YouTube search “Wai Kru” or “Wai Khru” and it will return numerous examples. The Wai Khru may appear strange and exotic,

but its two most important roles are: a.) to show respect to one’s teacher and the

relevant spirits/deities, and b.) to get the fighter’s head in the game. That

should sound familiar.

In the left hand shot

is Master Noi, one of the MTI instructors

What I learned that

will help me as a student of jissen budō

Three

things about my movement became apparent to me in Thailand. First, I sometimes

get sloppy with my guard. I’m not talking about letting it drop entirely. I

mean making it too slack or lackadaisical, or letting it drift. Second, I

learned that I tend not to deliver strikes while I’m retreating. I noticed a

proclivity in myself to associate advancing and attacking and retreating and

defending. In MT they emphasize that one should be striking when one is moving

back and away as well as when one is dominating. Third, I learned that I need

to optimize my footwork to the type of opposition I’m presently facing. One of

the errors that I was most frequently corrected for was getting too much of a

gap between my front and rear foot. Because we do a lot of movement at a range

disadvantage (i.e. mutō dori) or with

weapons, we tend to take bigger steps than do MT practitioners (also because we

bend our knees more deeply, which puts the feet further apart.) While I think

larger steps are appropriate for our movement, I can see the value of

conscientiously controlling that gap so as to minimize periods of weakened

balance—particularly in a one-on-one fist fight at the close ranges at which MT

fighters engage.

Closing notes

So

I guess my bottom line summary would be: If you have to fight a MT fighter in a

real world situation, don’t fight him in his domain. Throw a chair at him. Use

grappling. Get a weapon. Take it to the ground. But don’t go toe-to-toe in a knee

/ elbow range fist fight. That’s a sucker’s game.

I haven’t gotten into any of the logistical details of visiting MTI.

However, if you are considering going, feel free to contact me. I’d be happy to

provide information about things like what you should take, where to eat, how

to get there, etc. My contact info is: berniegourley@gmail.com

/ www.berniegourley.com